(Parts of this section reprinted with permission from our friends at The Ruckus Society, www.ruckus.org.)

What is Direct Action?

We who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open, where it can be seen and dealt with. Injustice must be exposed, with all the tension its exposure creates, to the light of human conscience before it can be cured.

In short, direct action means taking action yourself to create social change. Direct action is about recognizing your power as an individual - or group of individuals - to create meaningful change in the world, rather than relying on others.

For Tibet, direct action has played a critical role in raising the stakes for politicians and for the Chinese government. All of the Tibet movement's successful campaigns have relied on direct action in some form. It is one of the most powerful tools we have.

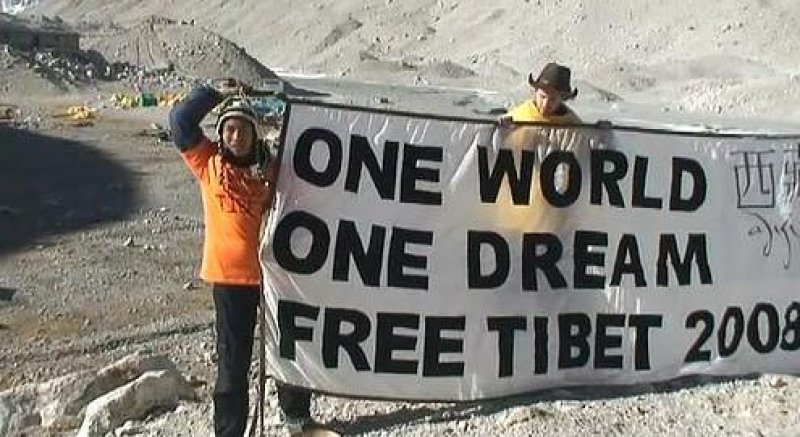

There is no single specific tactic that constitutes direct action. A protest can be direct action, a political theater skit can be direct action, a banner hang can be direct action - there is an endless number of ways to express your message in a nonviolent and creative way that will have a direct impact on your target.

Direct action has been a successful tactic in many movements throughout history. The success of Gandhi's campaigns in India, the campaign against Apartheid in South Africa or the U.S. Civil Rights Movement are just a few well-known examples. Since the beginning of the modern environmental movement, the campaigns against nuclear power, to save ancient forests, to end ocean dumping all have incorporated significant direct action components.

Direct action sometimes means breaking the law. Sometimes this kind of direct action is called nonviolent civil disobedience. The term "civil disobedience" originally meant deliberately breaking a law that you believe is unjust (for example, black and white people sitting together at segregated lunch counters in the American south during the Civil Rights movement), but it is often used now to refer generally to actions that might result in arrest. Actions that involve breaking the law are obviously not a tactic that should be employed lightly or without sufficient preparation and training. However, sometimes an injustice is too great to tolerate and a moment of opportunity presents itself to highlight that injustice through an action that involves breaking the law. For example, the head of your country's government is meeting with the President of China, and you happen to have access to the building right across the street from where they are meeting. You could get your message about Tibet to the two leaders, the public and the media by hanging a big banner with your message out of the window of that building. You could be arrested for such an action. It is up to you to ask yourself the question, "is what we will get out of this opportunity worth the risk?"

Again, please do not participate in actions that could result in your arrest without training, and without consulting a lawyer. If you are interested in such training opportunities, please contact SFT's international headquarters at info@studentsforafreetibet.org

The Foundations of Direct Action

As we discuss the uses of direct action, remember one thing: almost all successful actions occur within the context of an ongoing campaign. This means that political - not just logistical - work has been done long before the action takes place. This improves the chances that your action will be understood and be successful. This also means that you intend to follow up on your action. Intervention demands responsibility.

Here are some typical functions of direct action:

Announcement or Alarm. You have learned of a situation that demands immediate attention from the public. Your direct action is meant to shine a light on a hidden (or more likely, covered-up) danger or injustice that must not be kept secret.

Reinforcement. You have been campaigning on an issue, yet somehow the issue remains unclear to the public. You take action to clearly define the injustice, the parties responsible, and the solution.

Punctuation. Direct action can be used to sustain interest in a campaign. It is a dramatic reminder that the problem has not gone away. Direct action can serve as a milepost - like doing an action on the anniversary of Tibetan National Uprising Day (March 10) - or it may commemorate an outrage that should not be forgotten.

Escalation. A frequent use of direct action is to raise the stakes in an ongoing struggle. If a group of people who have not previously used direct action turns to this tactic, this sends a message that the situation has become critical, or that direct action is the last remaining avenue of pressing for a solution.

Morale. Sometimes when a group has suffered a setback and morale is low - or a group is tired from a long struggle - direct action can serve to raise the spirits and renew the struggle.

There is no doubt that direct action is a powerful builder of morale and community, but a word of caution on this last one: all of us who have engaged in direct action know its transformative effects. It leads to new discoveries about oneself, changes and intensifies ones relationship with fellow activists and people with you in the struggle, and can profoundly alter one's notions of power. It is intoxicating. But these personal-growth benefits are not the reasons for doing direct action. Your actions should make an objective change in the world - to literally change the course of history. The change you seek is the main goal of the action; empowerment, self-awareness and community are a bonus.

Civil disobedience is the assertion of a right which law should give but which it denies... Non-cooperation with evil is as much a duty as cooperation with good... All through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants… and for a time they can seem invincible, but in the end they always fall, always.

The Symbolic Nature of Direct Action

There has been some debate over "hard" vs. "soft" action. Some people advocate "harder" action and criticize "soft" action as being "just symbolic." This argument has at times even kept groups on different sides of the divide from working together effectively. But this argument shows a misunderstanding: all direct action is symbolic by nature.

When people say "hard" actions, they usually mean physical intervention or blocking. It is thought that hard actions cost the object of the action "a real price" and often end in arrests. "Soft" action on the other hand, is viewed as mostly symbolic - sometimes so non-interventional that it is described simply as a presence or witness. Demonstrations and vigils also tend to wear the soft label.

You can argue that the difference remains in the risk entailed by the action, or is difficulty. This is, in the end, a red herring. All actions, "hard" or "soft," have the same goal: to make an objective change in the world.

First, activists use direct action to reduce the issues to symbols.

These symbols must be carefully chosen for their utility in illustrating a conflict: an oil company versus an indigenous community, a government policy versus the public interest.

Then we work to place these symbols in the public eye, in order to identify the wrongdoer, detail the wrongdoing and, if possible, point to a more responsible option.

Frequently, usually by design, the symbolism and conflict are communicated to the wider public, using the media.

This symbolic treatment of the issue is, in fact, at the core of action strategy, and knowing this is key to understanding the tactic. The most important question is: could this action make an objective change in the world?

The most important, and therefore most difficult, thing about direct action is developing a sense of timing - when to seize a political moment. The second most important thing is creativity in designing an action, and fortunately that's a bit easier. Most of us are already creative in other areas, and this generally transfers well to direct action - especially when you've got a group of committed, focused activists with which to work and trade ideas.

There are a number of ways to practice creative brainstorming. Find out which one works for your group of activists. The most crucial factor in brainstorming, of course, is openness to new ideas from all quarters - action leaders must be ready to accept an idea that may come from a team member who has a "smaller" role, or is not as experienced in actions. But a close second is a commitment to stay at it until you get it right - hours, days or longer. Brainstorm until you're dry, then analyze what you've come up with and wait for your creative well to fill again.

Remember that formal indoor meetings are often the hardest place to be creative. Vary the location for your strategy sessions. Sit outside, or in a café or restaurant.

Openness to new ideas also includes the ability to see good ideas in other quarters, and appropriate them. You can't copyright an action, so don't be afraid to steal good ideas. Become a student of the ways other groups or individuals are taking action. Look for and at action as a tactic.

Finally, remember timing once again. A direct action trainer who has helped SFT used to say: "Timing may not be everything, but it's damn close." Action skills such as climbing or blockading are mechanical ones and most people can be taught these skills fairly easily. A sense of timing and opportunity is harder to develop. When examining other actions as a source of ideas, always work to understand the timing behind them.

Action Development

Although each action is different and in its course takes on a life of its own, there are a series of more-or-less standard steps to develop one. These steps presume that you are developing your action within the context of an ongoing campaign:

- Issue identification and clarification

- Picking the audience

- Setting the context

- Scouting

- Performing the action

The public has a brief, shifting attention span and a limited ability to absorb new information. That is why you as an activist must keep your campaign and action focused and on message. You must be able to answer three questions:

Presuming your overall campaign goals are clear, ask yourself again: Why is an action warranted at this particular point?

Does the proposed action have a reasonable chance of benefiting the campaign - of sending a message, moving the debate or raising its profile?

What about the political follow-up to the action: Will you be able to exploit the political opportunity your action seeks to create?

We recognize that everything is connected. But we can't attempt to campaign on everything at once, because the public won't hear us. You must define the issues clearly and as simply as possible. So decide which aspect of your campaign you're going to focus on right now. Then work to make everything about the action - location, banner slogan, even what your activists are wearing - speak to that.

People sometimes get impatient with this process of issue clarification and message development. But it is an absolute prerequisite to the next steps. Only with a clear understanding of your campaign and the issue can you pick up the target audience, set the context, and scout, plan and execute your direct action.

Picking the Target Audience

Picking the target audience is the next step in your action's development. It flows directly from your understanding of what needs to happen in the campaign at this point. In essence, you're saying: "I want my target audience to do this." Who has the power to give you what you want? Is it the general public, government officials, the Chinese government, or the CEO of a company whom you are trying to affect?

You might be inclined to think at first: "I'm sending a message to all of them." Good intentions, but fuzzy politics. Such universal messages are very rare. If you think you're sending a message to "all of them," if often means you haven't thought through your target audience well enough.

Each action should reveal what we're against and what we're for. We may be against several things: the Chinese government, the corporation who is helping the Chinese government, the politicians who won't stand up to China. But each of these players should be held specifically accountable for their specific actions. Nailing them on the specifics - who did what, and when did they do it - may be harder than issuing a grand indictment, but sends a much clearer message.

The principle also applies when you're thinking about what segments of the public you're trying to reach.

Setting the Context

Before making decisions about the place of action or other tactical choices we should pause and ask ourselves: Will the action be understood? It's an important consideration.

Actions don't occur in a void. They occur in a particular context, and being sensitive to the context increases the chances that your action will be understood. Do you want to do that hard-hitting action just before Christmas, for example, when folks don't like receiving bad news?

As activists we often have a more sophisticated understanding of an issue then the general public. For example, in the United States, polls have consistently shown that only about 15 percent of the American public is "interested and informed" on any given issue. This has several consequences for direct action campaigning.

First, we have to avoid jargon - specialized language, acronyms, or concepts understood in our movement, or amongst your group, but obscure to the general public.

Second, if you want to campaign on these more complicated issues, you must take time to establish the context before the action. There are many ways to do this. Releasing a report, holding a press conference or briefing, placing letters to the editor or advertising, can all help to establish context.

Third and most important, it's much easier - that is, more understandable to the public - to protest events rather than policy.

Finally, for all actions, remember the KISS rule: Keep It Short and Simple. The public has only a limited capacity to absorb new information over the short term.